As mentioned in What Is The Origin of Ikebana, ikebana as we know it dates back at least to 1462. You might wonder how it has survived over 500 years and many people (like me!) still enjoy practicing it.

As you can imagine, over the long course of history, ikebana faced many difficulties. Once it gained popularity, and other times it almost became extinct. Whenever it faced difficulty, ikebana found new audience and spread again.

Samurais and aristocrats – its original fans

Ikebana gained its popularity first among samurais and aristocrats in Japan. During the Edo period (1603 – 1863), ikebana also became popular among ordinary people. Both men and women used to enjoy it.

Ikebana crisis in 19th century

When Meiji period started and Japan opened its doors to the West at the end of the 19th century, people in Japan considered ikebana as outdated and it lost its popularity. With Meiji Restoration, Buddhist temples and samurai clans, both of ikebana’s main patrons, lost their prestige that they had once enjoyed. With no powerful patrons and very little interest among the public, ikebana was at the verge of extinction.

In the beginning of the 20th century, ikebana regained its popularity, with new audience. The Meiji government positioned ikebana and tea ceremony as two important subjects that young women should study at school. In most girls’ schools that were newly established in that period, ikebana became a compulsory subject. Since then, a notion that ikebana is practiced by women rather than men has prevailed.

New crisis for Ikebana

Ikebana faced with another crisis during World War II. The military-led government back then considered any art such as ikebana as unimportant or even as “evil extravagance.”

How Ikebana speed around the world

Once World War II was over, people were hungry for artistic freedom. When the flower exhibition was held in Tokyo in November 1945, only three months after the end of the war, so many people came to see the show.

Ikebana also found new audience.

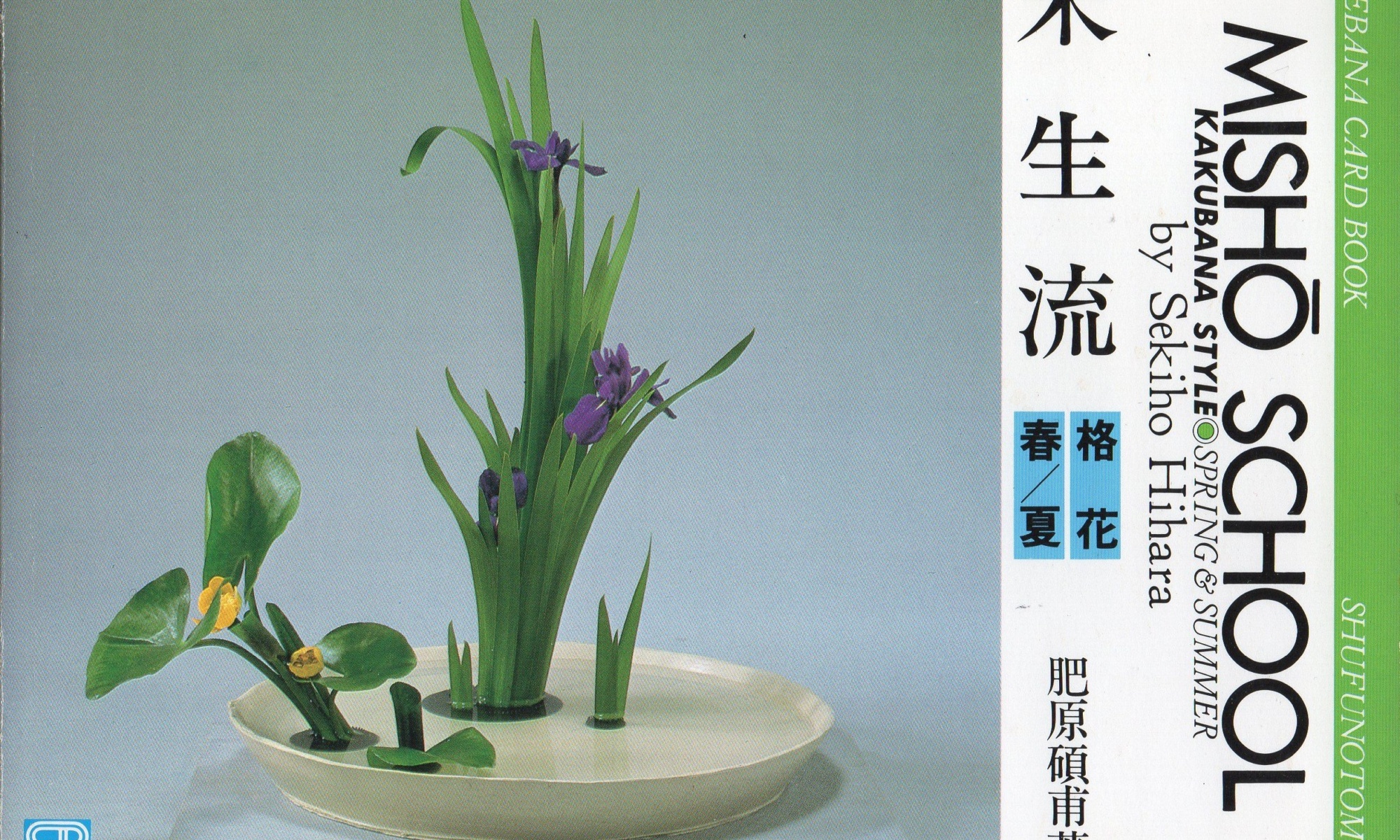

While Japan was occupied by the allies, many military officials were assigned to Japan from the US, and many brought their wives. Ikebana leaders in Japan in those years, including headmasters such as Sofu Teshigahara (Sogetsu School) and Houn Ohara (Ohara School), came up with a plan to hold ikebana classes for the wives of those military officials.

These wives took ikebana classes and obtained a teacher’s certificate while in Japan. So did wives of diplomats who were assigned to Japan from various countries. After returning to their own countries, those women started to teach ikebana in their own countries.

Although originated in Japan, now there are so many people enjoying ikebana around the world. We have to thank those wives of diplomats and military officials for spreading this wonderful culture worldwide.